Community Forum and Award

In October, we asked members of our community to respond to a few prompts about community, care and knowledge production. The responses blew us away. We carefully selected submissions from five of our fellow library workers and/or students who shared their brilliance with us.

We created this award to support the generative community which inspires and maintains up//root as a place for BIPOC to re-imagine, disrupt and grow together.

Please enjoy responses from our 2022 Community Award Recipients: Myisha Sims, Chinyere E. Oteh, olivier, Rosario Santiago and Cathy Messier.

PROMPT 1: Describe or show how a generative environment for knowledge production looks, feels, sounds to you?

Response By Myisha Sims

@my331

As a queer, fair skinned, working-class Black woman, I have been in circulation services for fifteen years at an academic library. My day-to-day work activities do not necessarily afford me the rank of a scholarly research nor am I a degreed librarian, and at times my perceptions are tinkered with as a less refined resource in the world of academia, but notwithstanding the academic slight I give attention to the opportunity to lean into being a more conscious listener unafraid to engage the various peoples, social communities, and academic authorities that frequent the library every day to help foster a good-natured environment.

One afternoon while I was staffing the circulation desk a few student assistants dredged up a conversation about the culture of caste systems and the blight of colorism that positions darker skinned women as less desirable and unpretty, often non-marriageable, and restrained in society. The scope of the conversation went many places and pinpointed a parallel to the Americanized version of caste hierarchy with its history of white supremacy, dismal misogyny, and its long-standing anti-Black attitude. At one point during the interaction, there was an internal moment that jumped up at me, and I thought, whoa, a conversation about oppressive similarities, mingling oppressions! Mingling oppressions reads now like such an unserious thought, but my mindset had to pause and consider my own attitude towards colorism: Now, while I am quick to admit that my identity as a queer, working-class Black woman usually regulates me to the less privileged margins in the world, far too often I am slow to acknowledge the favoritism that being fair skinned affords in a society hammered with colorism.

A gobsmacked realization to have to wag your finger at your own cultural short sightedness, and to examine how you present and act in your privilege. That interaction did fashion a desire to examine my position more thoroughly, however my steps to do so are still sluggard, and even if there were an expressway to cultural righteousness, it would seem two-faced, so I allow the slow but sure way about it.

Interesting enough though that for a better part of a year now, my work has afforded me the opportunity to be a contributing member to my library department’s Anti-Oppressive Interactions Task Force where the goal of our work is to become “a group of staff and librarians who will study how power is enacted in organizations and how to create and sustain anti oppressive environments” accompanied by a toolkit. As a group, during monthly meetings, we reflect on our findings in a think and share exercise (topic varies by facilitator), and one reflection asked what our own individual anti-oppressive toolkit would contain, and mine contained three things: protest music for inspiration; a smile to be more welcoming; and the principle of somebodyness. At the core of somebodyness is no shame. No shame in your skin color, no shame in the texture of your hair, no shame in your overall personhood, and to believe and say that “I am black, and I am beautiful,” and it is not that I lacked the confidence in understanding the beauty of being Black in multifaceted ways before it is just that since learning about the principle of somebodyness it now serves me as a small still voice as I continue to navigate librarianship as a light-skin Black woman dissecting her privilege in a society hammered by colorism.*

*Jewell, Tiffany This Book is Anti-Racist Frances Lincoln Children’s Books January 7, 2020 “Martin Luther King, Jr., What Is Your Life’s Blueprint? YouTube uploaded by Beacon Press 19 05 2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZmtOGXreTOU

PROMPT 2: How do you define care? What are some ways you express care in your community?

Photo of the author by Yoo-Jin Kang, @ykangphoto

Response by Chinyere E. Oteh

@ceochichi

CARE involves: Collectivity | Accountability | Reciprocity | Empathy

When I think of care, I immediately think of the self and the collective. Without both of these types of care I quite literally would not be alive today. I’ve had friends who texted me a simple, “Chinyere?” while I was in the depths of a depressive episode and I teared up and responded, ‘Hi” five minutes after receiving their text because that’s all I could muster. And yet I was so grateful he inquired about me in a most simple way so as to not overwhelm me. Friendship as accountability.

I’ve recently had the great satisfaction of walking up this long ass hill in my neighborhood while listening to Running Up That Hill by Kate Bush, which I’m pretty sure Fiona Apple makes reference to in a song on her last album that I very much resonate with. Caring for my body after the end of a short lived, intense, and debilitating abusive romantic relationship this summer feels. so. good.

And as a great believer in reciprocity, the care I receive and cultivate for myself, I must cycle back to my inner circle. I express care to my dear hearts (friends, lovers, my parents and my children and godchildren) by taking portraits of them to show them the beauty my eyes see when I get to bask in their presence. I send them voice memos of my meandering thoughts or myself reading my favorite passages by my favorite authors, and I DJ Chi them so they can cry through their sadness and dance in their joy alongside me. If you send me a song or a poem or a youtube clip or a meme that I enjoy, you best believe it's getting passed on to someone else I love. We can’t keep care all to ourselves, for we heal in relationship to each other. Without my inner circle and the giving and receiving that has enlivened me over the years I wouldn’t be here.

And yet, here I am. Still healing. Still loving. Still enquiring. Still napping. Still critiquing myself in many moments and giving myself grace in others. Still learning how to practice empathy beginning with myself. Still spiraling along my life’s map with learning moments that come more rapidly than ever before. And there you are. And I see you. Keep caring for your self, no matter how small the action may seem. Keep reaching out to your circle to ask for help and to share your gifts. And I hope to take your foto one day or drink coffee together or laugh raucously while walking thru a farmers market, that is, if our paths cross.

Response by olivier

@oh_otis

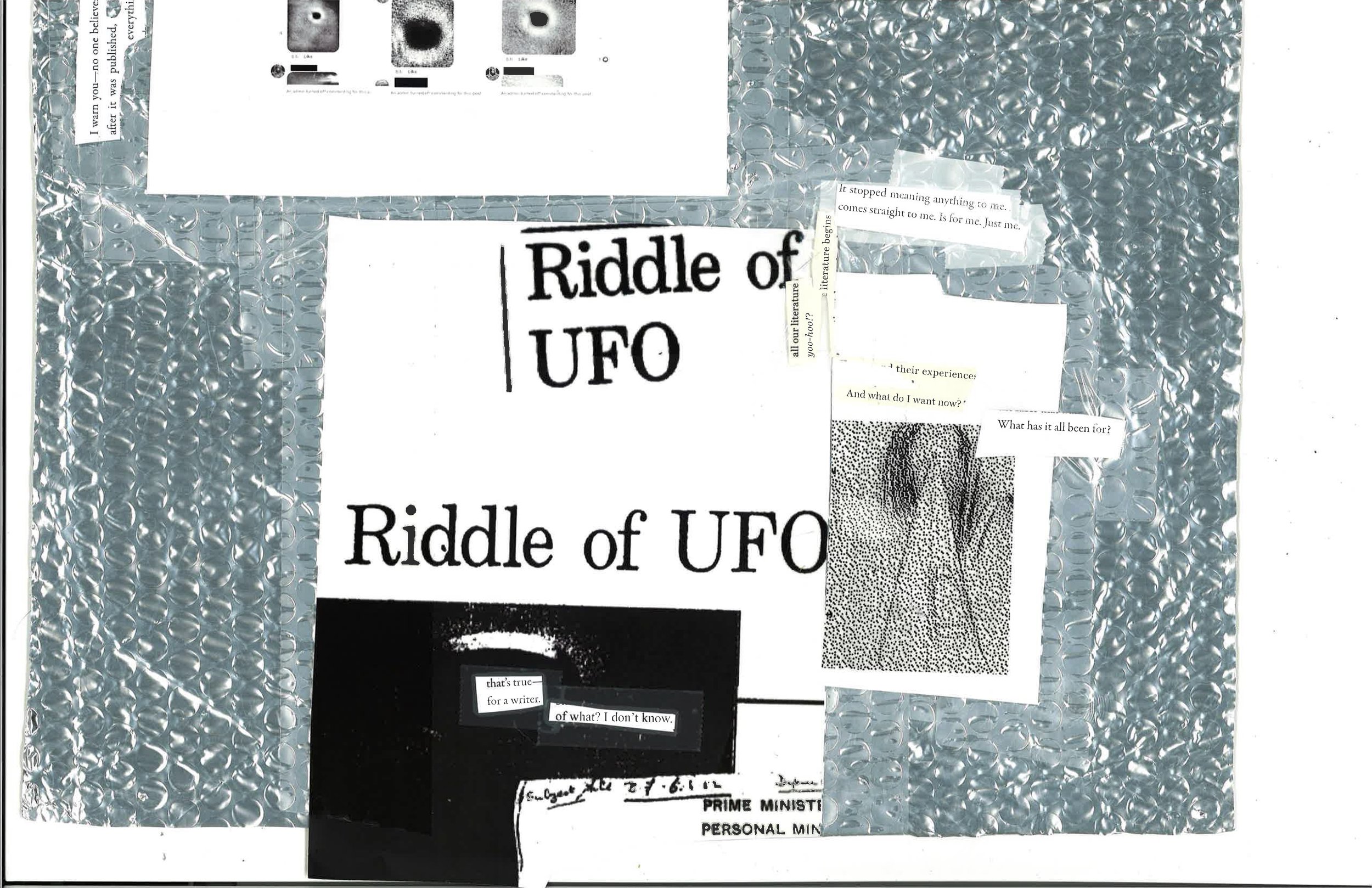

This box contains: 1 U.F.O.

One struggles to define oneself, like a book that is not taller than the height but longer than the width of a bookshelf, or like an object that fell off from one of the folders and no one could tell where it came from, and there is no apparent original order to scruple it back in.

As I wrote my 250th job application in my still-ongoing-6-month-long job search, there is this part that asked for the person having strong ties to their community- and that was it. There was no explanation to what is “strong”, what is “community”, what does having ties mean…

I have been in academia and the art world for a decade now. I cannot leave, because this is my only way to figure out a visa that allows me to stay in the good ol’ US of A. Once in a while, people will try to guess where I am from— I have an accent, but not distinct enough for people to know why a person with my colour and face has this accent. As an artist, we are trained to include where we were born and/or from and/or raised in our resumes, in our bios, in our CV, on our websites… in the essence of our work and practices. I see this parallel in the “provenance” in archives’ collections and artists’ files; records all tied together into one organisation, one person, one being, one unity. I have sorted random donated posters, postcards, invitations, etc. in artists’ files that essentially belong to more than 20 creators— in the absence of having a distinct community, I found myself relating to objects the most.

I was asked if I can write in my native tongue in a second round interview, I stuttered (in English) and said, ‘Y-Ye-Yes? I can?’ The search committee paused and said, ‘Well, in metadata, you can write whatever you need to include, so if you can write in xxxxxxxxx that would be great.’ I found myself starting to explain my native language isn’t a written language, and that it is a dying dialect that the xxxxxx Government is trying to kill off, but it could be written, if I want, but it is not an ‘official language’. I told them there are a lot of characters that are not supported by the majority of the fonts, and…then, I remember I have searched through their collections, there isn’t anything from my place of origin or in my native language. In fact, there isn’t anything from Xxxx Xxxx in most academic libraries. Once in a while I came across an artist or writer also from xxxx xxxx but their records got absorbed into the categories of xxxxx xxxxxxxx or xxxxxxx.

Recently, I finally got my chosen name and gender to be updated in my Xxxxxxx passport. I could not get it updated with my ‘original’ passport that sent me to the U.S. though. Who am I in here? How do I prepare to be myself after I leave?

The care of my community is the care for the community of the misidentified- no- it is the community of unidentified. Like ‘U.F.O.’ (Unidentified Flying Objects) that are now transitioning to ‘U.A.P.’ (Unidentified Aerial Phenomena), my body, my voice, my gender, my slangs, my accent, my place of origin is transitioning. In 25 years, my place of origin will have their name officially changed. In fact , a lot of people have already started using its ‘new name’—it is embarrassing, horrendous, and dreadful to know there is this guilt living inside of me: I have left and never will return.

An object that is unidentified, sometimes, failed the appraisal part of archival processing. But mostly, they are in the Misc. file and with little to no description. Like a U.F.O., they are items with potential metadata to be extracted, waiting for the right tool, the right archivist, the right researcher, the right reader, the right believer, the right sceptic.

Care is to be with the unidentified. To be in the opacity; opacity is an unknowability (Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation). As Glissant defined opacity as “a diversity that exceeds categories of identifiable difference”, I live as a person that contains no method to explain and expand. My community of unidentified objects, perhaps accidents of incidents and incidents of accidents— when an object is discarded, I leave a sentence in processing note; in the sentence, I/we thrive and continue to be unidentified.

Response by Rosario Santiago

@epistolarybot

I believe that care is a collective effort. The intricacies of care should both be seen as a framework and an active practice that is embedded into our everyday lives. I know care because I have cared for someone and because someone has cared for me. It must be our goal to care for one another in ways that disembody what the western world considers a society of individualism, where I am expected to center myself in my life and in the life of others, where I should not only participate in deathly competition but revel in it, and where care is ultimately defined within the suffocating and debilitating constraints of capitalism. Thus, to care for ourselves and one another is a radical, decolonial act. Care is much more than nurturing and empathizing for one another, but the active resistance to white supremacist ideology.

My lexicon for care stems from the book Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories From the Transformative Justice Movement. This collection of essays edited by Ejeris Dixon and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha has changed the way I view myself and the relationships I form. The idea of a “decolonial care” was once very overwhelming and confusing to me, but with Beyond Survival, I have been able to conceptualize and practice living a life that centers transformative justice. The biggest fear I have is stumbling into the unknown. How do we imagine a community where we take care of each other, where we accept that we will make mistakes and cause harm, all the while abolishing systems of oppression that we consistently lean on because it is all we know? I love the essay “Pods and Pod-Mapping Worksheet” by Mia Mingus for the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective in the Beyond Survival book. This piece has been useful to me in being able to name those in my community that I can lean on in times of a crisis, which then helps me decenter an institution (like the police, a hospital, or my college) as a source for help when more often than not, it will continue to harm me. There’s a throughline within all of the works in this book, and it’s on how we can center transformative justice in our communities so that we can address and mend problems of violence and trauma.

We can begin to heal through a collective care because we have each other to lean on, as well as strategies of what to do when a problem does arise. I try to fill out a Pod Mapping sheet at least once a year, and I also share the worksheet with my friends. I am vocal about how much their support and care means to me and how much I value when they come to me for advice, help, or just an ear to listen. I am extremely grateful that the reason I am able to have these conversations is because of the people who have come before me to do the complicated and rewarding work of transformative justice, which was often by queer disabled activists of color. It is a cycle of care that I must believe is ongoing for the sake of liberation and dismantling a white supremacist rhetoric that only values the production and labor of a person and not their life. A community before me has cared for this work so much that they’ve set the wheels in motion for a decolonized future, and I care about my ancestors, mentors, my contemporary community, and the future generation so much that I want to continue that process. It is truly about stumbling, tripping, and fumbling towards transformative justice so that we can imagine, manifest, and embrace a future of collective decolonial care.

PROMPT 3: Read and engage one of the following works published on up//root. What ideas, disagreements, or questions arise? Please share your thoughts.

Response By Cathy Messier

@cathytown

In response to “Latinidad” as Erasure: Words from a Critical Discussion on the Single Narrative of Latinidad.

Part of me is kicking myself for waiting so long to turn this response in, even though I know it’s entirely due to the anxiety and stress of being in my first semester of grad school for Library and Information Science, after a decade of not being a student in any capacity. The other part of me is glad I waited until today. I just finished putting up a Latinx Heritage Month display at my public library job in Massachusetts, where I work as a part-time circulation assistant, and where I am the only Latinx staff member in Adult Services (out of a staff of a little over 30 employees). The thoughts I had while putting up my display, which I honestly have all the time, are ones I recognized in the work “Latinidad” as Erasure: Words from a Critical Discussion on the Single Narrative of Latinidad.

The quote I most related to in this piece was “I am eternally confused here,” spoken by Cristina Fontánez Rodríguez. Throughout my life, my concept of my own Latinidad has been entirely dependent on the context of my surroundings. My parents are Colombian immigrants who came to the United States, specifically Queens, New York, in the late 80s. I grew up in Jackson Heights, Queens, an area known in New York as very ethnically diverse, with a particularly large Colombian population. During my childhood and adolescence, it never felt like there was a superficial sense of unity surrounding being Latino as a whole - the nuances and distinctions between each country’s language and customs were obvious, and our Queens community gravitated much more toward pride associated with our own countries rather than generalized “Latino” pride. In contrast, when I moved to Massachusetts at age seventeen to go to college in a predominantly white university and truly felt like a racial minority for the first time in my life (the first thing a fellow student said to me was, “Are you ethnic?”), Hispanic and Latinx pride suddenly acquired a whole new significance. In a way, it was a defense mechanism against pretty frequent racist comments. After college, I moved back to New York for several years, and then back to the Boston area to work in libraries, historically very white spaces, which is very much still the case in the Boston area. With each move, my specific ways of embracing my heritage and ethnicity either shift and become something new, or revert to old patterns. My sense of self as a Latinx woman has felt like an extended ping pong match.

Besides relating to many ideas brought up by the different presenters, I felt challenged by certain parts in a way that I feel was necessary. I realize, thanks in part to Gabby Womack’s comments on the use of the Spanish language as gatekeeping, that part of what I think makes me a valuable asset in my job is the fact that Spanish is my native language and I read and write in Spanish as well. We have many Spanish-speaking immigrant patrons, and I am often the only person around who can speak with them. While that is undeniably a good thing in terms of my ability to help patrons get the resources they seek, I also need to unpack and perhaps unlearn some biases about what makes someone a “useful” Latino, particularly in white-dominated workspaces. For example, in my Boston-area neighborhood, there are many patrons who are immigrants from El Salvador and Guatemala. I know there is someone out there who would be way more equipped than I am to do outreach and build relationships with those patrons, due to deeper knowledge of their specific communities, even if that person didn’t actually speak fluent Spanish. Not to mention how this mentality, as Gabby Womack pointed out, leaves out indigenous languages altogether. When Yvette Ramírez spoke about how Queens was the traditional homeland of Munsee Lenape peoples, I felt ashamed to have not already known that, in addition to not knowing very much about the indigenous history of Bogotá, Colombia. I appreciated the reminder that even though I see why I would gravitate toward a more homogenous approach to Latinx identity in my workspace, it is not an excuse to avoid digging deeper.